The Language That Wasn’t Meant to Exist!

“Una nazione è una lingua, un’anima, un popolo.” — Pier Paolo Pasolini

Prologue

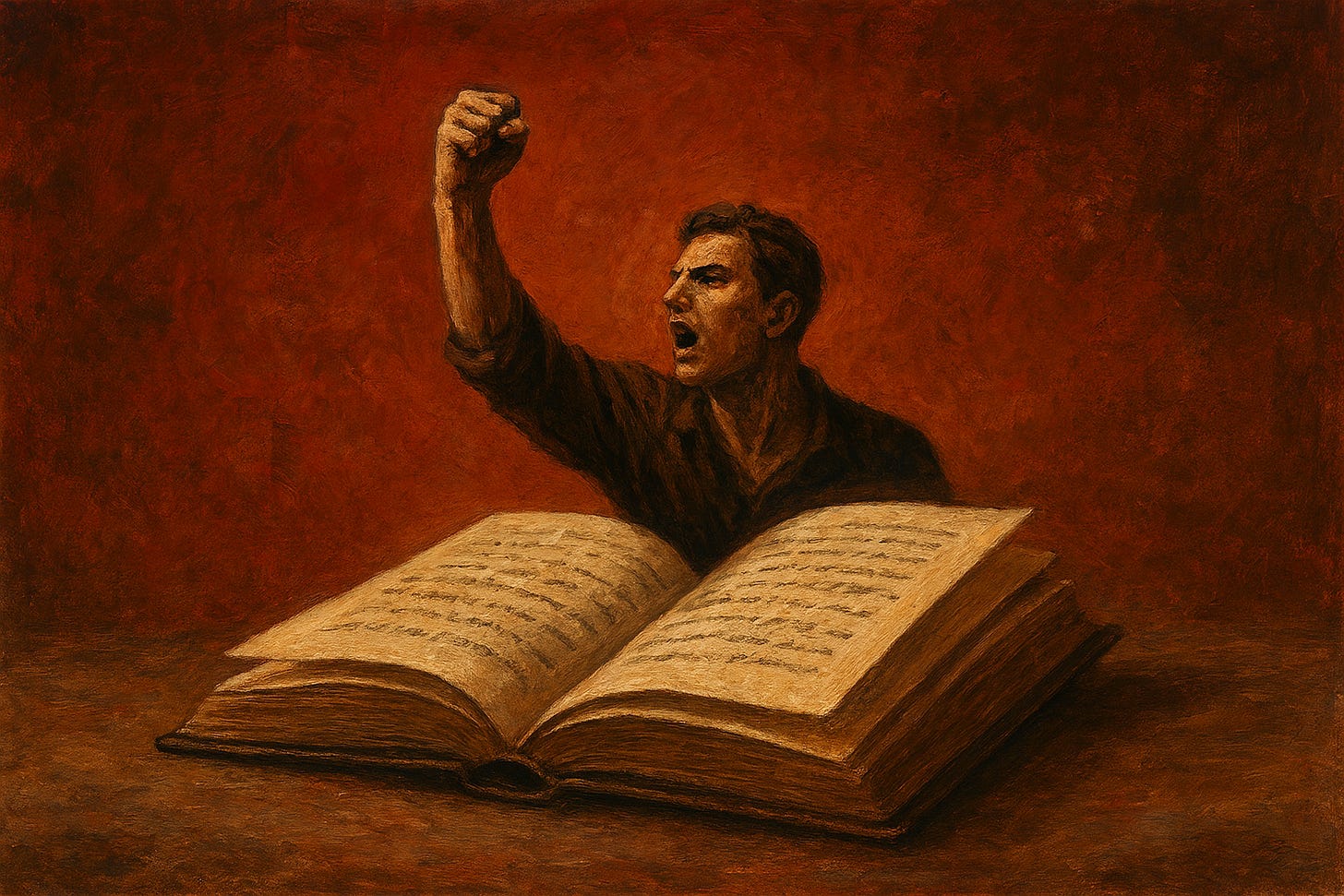

There’s nothing natural about a language. Every word is a conquest, every rule a healed wound. This is the story of a language that wasn’t meant to exist. And yet, it learned how to be heard.

The Language That Didn’t Know It Was a Mother

Italian was born from a paradox: it descends not from the polished Latin of Cicero’s marble rhetoric, but from its scrappy, streetwise sibling—latino volgare. This was the language of soldiers cursing in the trenches, merchants haggling in crowded forums, mothers scolding children in smoky kitchens. It was the Latin that bled, bent, and broke across provinces, mutating in the mouths of peasants and legionnaires. While the Senate clung to its syntactic purity, the empire’s underbelly was already speaking something else—something raw, alive, and destined to outlive its master.

This so-called “vulgar” Latin wasn’t a single dialect but a swarm of regional variants, each shaped by local tongues and tribal ghosts. In Gaul, it tangled with Celtic; in Hispania, it absorbed Iberian grit; in the Italian peninsula, it danced with Etruscan echoes and Oscan bones. The Roman road network didn’t just move troops and taxes—it spread phonemes like wildfire. A centurion from Benevento might die in Britannia, but his accent would linger in the soil.

Christianity, ironically, helped vulgar Latin rise. Missionaries needed to preach to the masses, not the magistrates. When Jerome translated the Bible into the Vulgata in the 4th century, he wasn’t just simplifying scripture—he was legitimizing the people’s tongue. The Church, in trying to control the Word, accidentally democratized it.

By the 6th century, the empire was rubble, and Latin was cracking. The elite clung to their classical Latin like a dead language cult, while the rest of the population forged ahead, speaking a proto-Romance that no one dared write down. But the cracks are visible. The Veronese Riddle (9th century) reads like a riddle and a confession: “He plowed white fields, held a white plow, sowed black seed.” It’s not Latin anymore. It’s something else. Something new.

And then came Dante. In De vulgari eloquentia, he draws a line in the sand: Latin is learned, artificial; the vernacular is natural, maternal. He doesn’t just defend the vulgar tongue—he crowns it. What was once dismissed as bastard Latin becomes the embryo of a national language.

Italian didn’t erupt—it eroded its way into being. It wasn’t born in a palace, but in the mouths of the anonymous. It’s a language forged in the friction between empire and collapse, between silence and survival. And every word we speak today carries the ghost of that rebellion.

Continua a leggere con una prova gratuita di 7 giorni

Iscriviti a Enrico Maria Marigo per continuare a leggere questo post e ottenere 7 giorni di accesso gratuito agli archivi completi dei post.